Il y a beaucoup à dire et à corriger sur le Mosquito qui s’est écrasé dans la forêt de Brou dans la nuit du 26 au 27 juillet 1944.

Il y a 80e anniversaire du crash (j’écris ceci en novembre 2023), il est temps de réorganiser toutes les informations. Cette page et les liens seront donc mis à jour au cours des prochains mois.

En attendant, voici un aperçu qui a été rédigé en 2021 pour le magazine de l’Amicale des Anciens des Maquis de l’Azergues.

Contexte

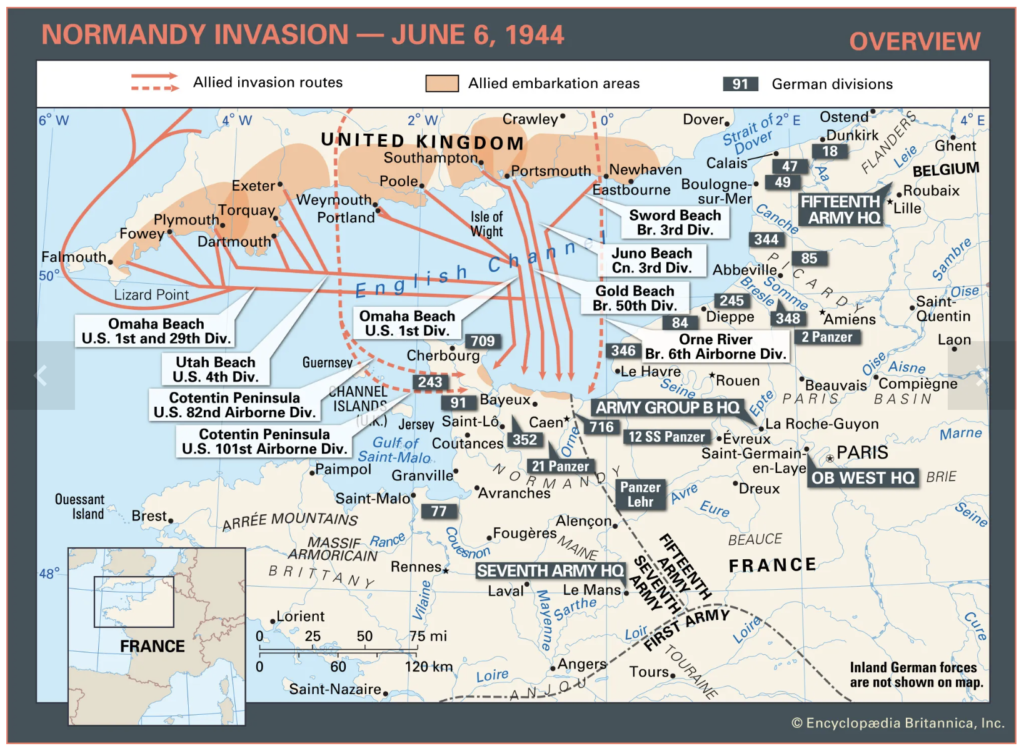

Le 6 juin 1944, des troupes du Royaume-Uni, de France, des États-Unis et du Canada ont attaqué les forces allemandes sur la côte nord de la France. Une vaste opération impliquant des ressources militaires aériennes, terrestres et maritimes a marqué le début de la campagne de libération de l’Europe du Nord-Ouest occupée par les nazis.

A 21h20 le soir du 26 juillet 1944, 178 bombardiers LANCASTER ont quitté divers aérodromes anglais ; leur mission était de détruire la gare de triage de Givors. Les 9

« PATHFINDERS » De HAVILAND MOSQUITOS qui devaient accompagner les LANCASTER provenaient du 627e Escadron, RAF Woodhall Spa, un aérodrome de l’Est de l’Angleterre dans le comté du Lincolnshire.

Le DE HAVILLAND DH.98 MOSQUITO était un avion de combat britannique bimoteur et polyvalent servi par deux membres d’équipage. Il a été construit principalement en bois – car le bois était le seul matériau disponible gratuitement, d’où son surnom de « WOODEN WONDER » (le bois puissant). C’était l’un des avions opérationnels les plus rapides au monde et il a donc décollé environ 2 heures après les LANCASTER pour un ralliement au-dessus de Lyon.

Le rôle du PATHFINDERS était de larguer des fumigènes pour signaler la zone à bombarder dans la gare de triage de Givors pour aider à placer avec précision la charge utile des bombardiers lourds. Givors avait été la cible de nombreux bombardements pendant la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale par la Luftwaffe, la RAF et l’USAF. Depuis le débarquement, une fois de plus, les gares de triage à travers la France étaient devenues le centre d’intenses bombardements pour contrecarrer le mouvement des réserves et du fret militaire à travers l’Europe par l’armée allemande. L’utilisation de PATHFINDERS a été conçue pour réduire les pertes civiles en augmentant la précision.

Cependant, dans la nuit du 26 au 27 juillet 1944, il y eut une importante tempête électrique à travers l’Europe, et l’énorme force de bombardiers aéroportés du affronte l’orage pour larguer sa cargaison mortelle. Alors que le météo laissait penser que peu de forces allemandes seraient aéroportées vers la cible, la formation de bombardiers a été interceptée en route dans le nord par des JU88 et des ME410. Malgré la visibilité proche de zéro, les fortes pluies et le tonnerre continu, l’impératif stratégique de la mission signifiait que l’annulation de l’opération pour quelque raison que ce soit n’était pas une option pour les alliés.

Moins de trois semaines après l’invasion, il y avait encore de violents combats dans le nord de la France. La force de bombardiers a donc dû emprunter un itinéraire détourné vers son objectif pour éviter d’être ciblée par des forces amies – une perspective amplifiée par le temps épouvantable. Leur chemin les a conduits au sud-ouest le long de la Manche, traversant la côte française jusqu’en Bretagne, puis descendant vers le sud pour approcher Givors par l’ouest. Le caractère tortueux du parcours et la météo placent les MOSQUITOS à la limite de leur rayon d’action.

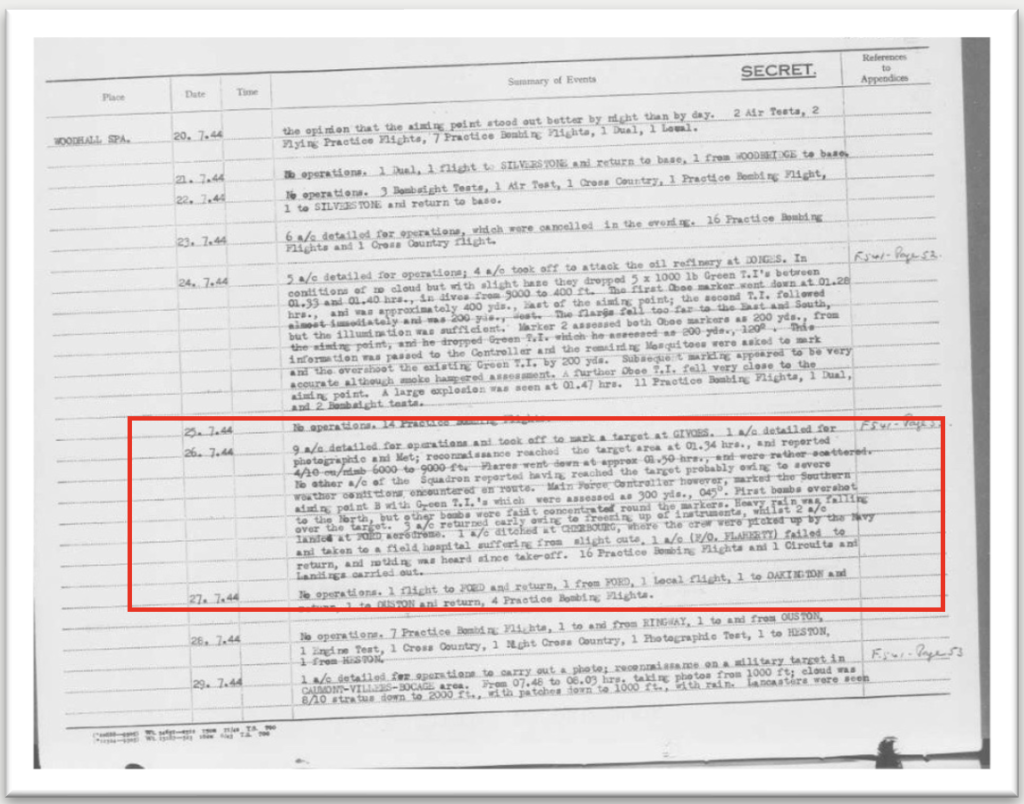

Sur les neuf De HAVILAND MOSQUITOS, seulement trois ont atteint la cible. Le rapport de l’escadron pour la nuit indique.

« 9 avions pointés pour les opérations ont décollé pour marquer une cible à GIVORS. Un avion pointé pour la photographie la météo et la reconnaissance a atteint la zone cible à 01:34hrs … tous étaient plutôt dispersés… »

Le livre de rapport des opérations fournit plus de détails, prouvant que trois avions ont bien réussi à atteindre la cible, mais les marqueurs qu’ils ont largués étaient très dispersés et imprécis. À son retour, l’un d’entre eux a manqué de carburant et a fini par amerrir dans la Manche, il a été récupéré par la Marine. Parmi ceux qui ne sont jamais arrivés, un n’a pas pu identifier la cible et quatre ont dû écourter la mission et revenir plus tôt à cause de la formation de glace sur les ailes.

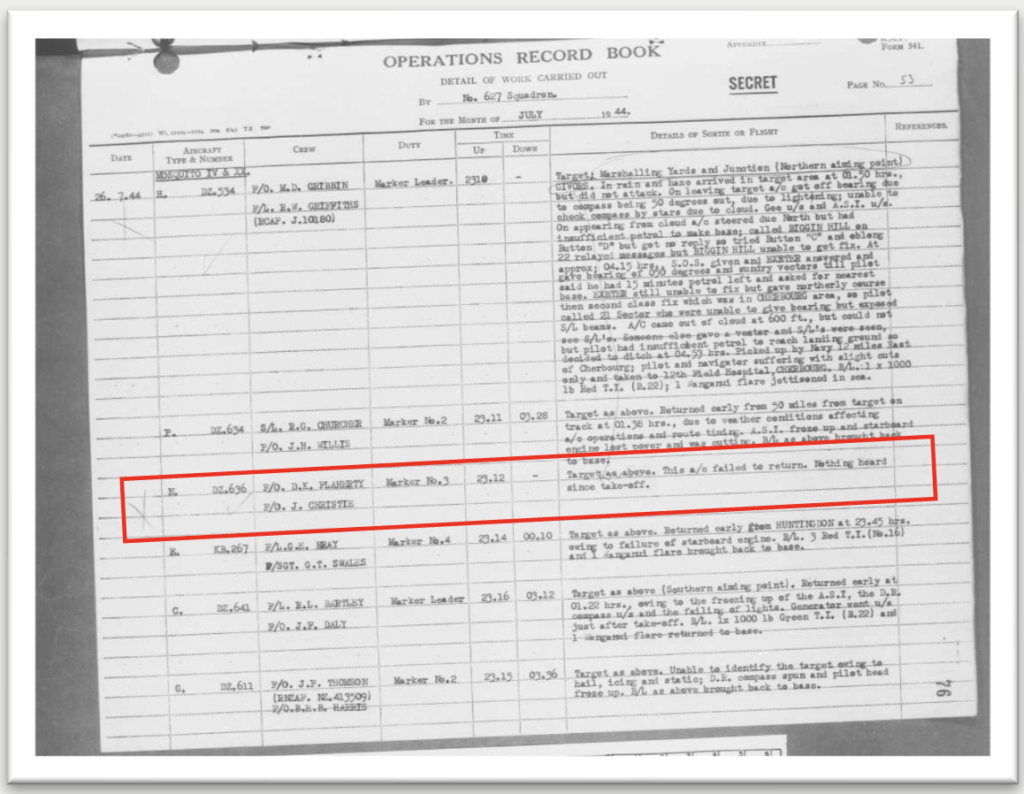

DZ636 avait été désigné comme MARQUEUR N°3 – Le livre de rapport des opérations nomme l’équipage de deux personnes et précise qu’il n’est pas revenu.`

Nous savons maintenant que cet avion s’est écrasé dans la forêt de Brou au-dessus de Ternand cette nuit-là, tuant le pilote et le navigateur.

Il est impossible d’être certain à 100 % de la cause de l’accident.

DZ636 n’est pas arrivé dans la zone cible. Il y a des témoignages pour préciser qu’il ne portait pas de charge utile de bombe. Cependant, la charge utile n’était pas des explosifs traditionnels, mais des fusées éclairantes, et donc un œil non averti aurait pu se tromper.

Plusieurs facteurs ont potentiellement contribué à l’accident.

Tout d’abord la météo, comme je l’ai mentionné ci-dessus, il y a eu un orage électrique massif à travers l’Europe, qui a mis fin à une vague de chaleur prolongée. Une telle tempête a provoqué du givrage sur les ailes, une désorientation due au dérèglement des équipements de navigation et a sans aucun doute contribué à l’inscription au journal de bord opérationnel :

« Target as above (Givors). This aircraft failed to return; Nothing heard since take off. »

« Cible comme ci-dessus (Givors). Cet avion n’est pas revenu ; rien n’a été entendu depuis le décollage. »

Deuxièmement, l’inexpérience du pilote.

The Crew

Il y avait deux membres d’équipage; le pilote Dennis Kieran FLAHERTY et le navigateur était John CHRISTIE.

John CHRISTIE est né en octobre 1911 à Brechin en Ecosse. Il s’est enrôlé dans la RAF en août 1934 à l’âge de 23 ans. Il a gravi les échelons et était sergent d’aviation lorsque la guerre a éclaté. Il était stationné à Poix en Picardie avec la 53e escadrille. Il était observateur à bord des bombardiers de Blenheim pendant la bataille de France et s’occupait de missions de reconnaissance alors que les Allemands avançaient sur la France. Il avait travaillé avec la même équipe pendant 18 mois. le Flying Officer Alaistair PANTON, Pilote et le mitrailleur AC2 BENCE. (Aircraftman Second Class)

Le 11 mai 1940, ils sont abattus derrière les lignes ennemies en Belgique. Grièvement blessé, CHRISTIE a réussi à revenir au Royaume-Uni dans ce qui ne peut être décrit que comme un exploit fantastique de bravoure et de ruse. PANTON a repris des missions et plus tard cette année-là il été capturé par les Allemands. Il a passé le reste de la guerre en tant que prisonnier et, après une carrière de 35 ans dans la RAF il a atteint le grade de commodore de l’air. AC2 BENCE a perdu une jambe et a été arrêté dans un hôpital français. Plus tard dans sa vie, il est devenu directeur d’école dans le Gloucestershire.

CHRISTIE a été promu en août 1943 FLYING OFFICER, il a été affecté à l’escadron 627 sur MOSQUITOs en juin 1944. C’était un officier expérimenté, et comme c’est souvent le cas, il aurait été associé avec un officier moins expérimenté pendant les opérations.

Flying Officer Dennis Kieran FLAHERTY l’officier moins expérimenté était, né le 8 octobre 1920 à Bradford dans le nord de l’Angleterre. Je pense qu’il était enfant unique. Il s’est enrôlé en septembre 1940 et a commence son service actif en juillet 1943. À la fin de 1943, la RAF manquait cruellement d’équipage, sa carrière de pilote a commencé par une formation initiale en vol en mars 1944. Après s’être entraîné à piloter des MOSQUITOS et avoir été affecté à l’équipage opérationnel de l’escadron 627 en juin 1944, il n’aura survécu que 51 jours.

Le dernier facteur est peut-être le plus subjectif. Je n’ai aucune preuve, mais cela semble correspondre. Ian Stevenson a mené une enquête sur 2 bombardiers LANCASTER du même raid sur Givors qui se sont écrasés aux alentours de St IGNAT près de Clemont-Ferrand. Il détaille comment les conditions météorologiques, la route et le nombre considérable d’avions impliqués dans l’opération ont entraîné plusieurs collisions en vol. Dans ses recherches, il détaille un « avion mystérieux » qui est entré en collision avec un LANCASTER – il n’est pas impossible que cet « avion mystérieux » soit le MOSQUITO DZ636 responsable de cette collision en vol qui a contribué à la perte de contrôle du pilote et à la chute de l’avion.

En résumé, nous ne pourrons avancer que quelques hypothèses sur les causes de l’accident :

- Il y a eu, sans aucun doute, une tempête féroce sur de larges pans de l’Europe cette nuit-là, mettant fin à la canicule.

- D’autres MOSQUITOS de l’escadron avaient connu des problèmes de givrage des ailes, de givrage des moteurs et d’autres pannes catastrophiques résultant de la tempête, y compris une désorientation due à la panne des instrument

- Rien n’indique que le DZ636 ait été abattu ; sa chute a été plus probablement due au givrage, à l’incapacité de naviguer, à un coup de foudre direct ou même à une collision en vol.

Quoi qu’il en soit, ces deux officiers d’aviation ont en effet perdu tout contact très tôt. Malgré cela, ils ont poursuivi cette mission bien qu’elle fut ce qu’un pilote qui a survécu à l’opération a décrit comme l’un des vols de huit heures les plus fatigants et les plus exigeants de tous les temps. Sans aucun doute, les Flying Officers FLAHERTY et CHRISTIE sont morts en héros, seuls sur une colline déserte. Les habitants de Létra et des environs, ont traité les corps avec respect et dignité et ils resteront toujours dans les mémoires.

En juillet 2018, j’ai visité Thorpe Camp, la base du 627e Escadron à Woodhall Spa. C’est maintenant un musée privé. Sur le mur, j’ai trouvé une photographie du Flying Office Dennis Kieran FLAHERTY . Je fus ravi, j’avais commencé à penser qu’aucune photo n’existait. Mike HODGSON, le fondateur du Thorpe Camp Visitors Centre, m’a dit qu’après la guerre, les survivants du 627e Escadron se réunissaient une fois par an. Au départ, il y avait de nombreux pilotes, navigateurs, personnel au sol, WAAFS (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force), et leurs conjoints. Lentement au fil des ans, les chiffres ont diminué. Aujourd’hui, il n’y a plus de réunions.

« À chaque réunion, ils regardaient souvent cette photo », a déclaré Mike HODGSON, « mais aucun d’entre eux n’a jamais reconnu Dennis. »

La vie du Flying Officer Dennis Kieran FLAHERTY en tant que pilote opérationnel dans la RAF a été si courte que personne ne se souvenait même de lui.

- Un million d’hommes et de femmes ont servi dans la Royal Airforce avec des volontaires de tout le Commonwealth britannique, d’Europe de l’Est, de France et même d’Allemagne.

- Sur les 125 000 membres d’équipage, 28% ont été grièvement blessés ou faits prisonniers.

- 44% ont été tués – le taux de perte le plus élevé de toutes les unités alliées.

Pour toutes ces raisons, il faut souligner ce qui s’est passé après la mort de CHRISTIE et FLAHERTY ; on ne saurait trop insister sur la contribution de la communauté locale à la préservation de leur mémoire.

Sans cette tombe, du cimetière de Létra, la mémoire de FLAHERTY en particulier, qui n’a aucun parent survivant, serait perdue à jamais. C’est pourquoi j’essaie d’aider l’International Bomber Command Center dans le Lincolnshire, en Angleterre, à poursuivre son travail et de mémoire de réconciliation, et de reconnaissance, du sacrifice du hommes et femmes qui ont tant donné pour sauver les libertés dont nous jouissons aujourd’hui.

SOURCES

Liste des photographies ci-jointe.

Crew of DZ 534 rescued from English Channel.jpg (L’équipage du DZ 534 sauvé de la Manche) SOURCE: © United Kingdom National Archives

FO Dennis K Flaherty.JPG (Pilote du DZ 534 – Dennis K Flaherty) SOURCE: Photo © THORPE PARK VISITORS CENTRE, Woodhall Spa Lincolnshire. (Use of photo preserved by Martin Baker.)

Funeral of FLARTY and CHRISTIE.jpg ( Funérailles de FLARTY et CHRISTIE) SOURCE: Photo property of © David CHRISTIE (Nephew of John Chris’e—use of photo preserved by Martin Baker.)

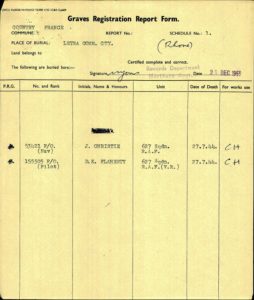

Graves Registration Report – 21 Dec 1959.JPG – ( Rapport d’enregistrement des tombes – 21 décembre 1959) SOURCE : Review of burial site of CHRISTIE and FLAHERTY in LETRA ©Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Highlighted Flight Record Book.jpeg ( Carnet de vol en surbrillance – Affichage des détails du vol de Mosquito DZ 534) SOURCE : © United Kingdom National Archives

Highlighted Operation Record Book.jpeg ( Highlighted Opera’on Record Book.jpeg – Affichage des détails de l’opéra’on de l’escadron) SOURCE : © United Kingdom National Archives

John CHRISTIE FO RAF. JPG ( Photographie du navigateur du mous’que DZ 534) SOURCE: Photo de famille appartenant à David CHRISTIE – Neveu de John – Copie également fournie par David CHRISTIE au Maire de Létra)

© Martin Baker 2023

Coming Soon

The story of the The MkIV de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito

Details of the Crash site in the Forêt Départementale de Brou

Some parts recovered from the crash site and the stories since their discovery.

The funeral of the two airmen and their subsequent burial in the CWG at Létra.

Flying Officer 53421 John CHRISTIE Royal Air Force.

Flying Officer D155505 Dennis Kieran FLAHERTY, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve.

This post is also available in:

English

English